CLEF Newsletter - November 2023

“When I think of the sacrifice yet to be offered and the hearts and homes yet to be made desolate before this dreadful war is over, my heart is like lead within me, and I feel at times like hiding in a deep darkness” (A. Lincoln, Nov. 18, 1863, en route to give a brief address at Gettysburg…).

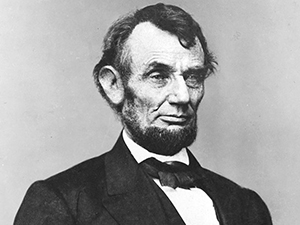

Under the circumstances, the last thing on Mr. Lincoln’s mind might have been thanksgiving. No President before him had ever been more hated and roundly criticized. He was attacked in every way both professionally and personally with the visceral, invective and vindictive verbal venom reserved only for those most deeply reviled and repulsed. If it hadn’t been for his family and at least most of his cabinet and maybe a few congressmen, he would have had no friends at all, or so it seemed. Hundreds of thousands of lives had already been lost in this “mighty scourge of war,” and there was no end in sight. With antiwar feelings boiling over and Northern Democrats launching a peace movement to stop the war and bring Union troops home, Lincoln had no peace. Even within the Republican ranks, former allies were now beginning to jump his ship of state. His generals were failing at every turn, and what few victories they had garnered were not followed-up with any decisive blow. The mounting death toll, besides weighing on his own heart, was weakening the resolve of even his staunchest advocates. All were beginning to wonder if the cause of the union had already failed, and the continued sacrifice of more lives was both futile and fallacious; and yes, he was being indicted for that too. On top of all this, he and Mary were still bitterly mourning the death of their son Willie to scarlet fever, not a year and a half earlier. Now the weight of the war was bearing down hardest. Four months prior, one of its hardest and most heartbreaking battles had been fought at a little Pennsylvania country town called Gettysburg where over fifty thousand casualties were suffered on both sides. But General Meed had failed to pursue Lee who, though defeated, was allowed to escape and regroup his army. Now just two weeks ago, a solemn ceremony was held to dedicate a national cemetery for the soldiers who had died there. Lincoln had not been invited, but wanting to make a brief statement about the larger meaning of the war, was able to weasel a begrudging seat on the platform for “a few appropriate remarks” after the main speaker, a most celebrated orator of the day, had finished. The speaker, Edward Everett, spoke for two hours. Lincoln’s address, about 270 words, lasted two minutes. “Some of his listeners were disappointed. Opposition newspapers criticized the address as unworthy of the occasion, and some papers didn’t mention it at all.” Lincoln himself thought the speech was a failure. The first words he muttered when he sat down were “That didn’t scour;” a phrase used back then for failing to accomplish the task (yet in retrospect, Everett later acknowledged that Lincoln had said more in his two minutes of remarks than he had tried to express in two hours). Now back in Washington, candidates were lining up to displace him in the next election, both Republican and Democrat, and all were favoring a truce, ending the war, rescinding the emancipation proclamation, and putting things back as they were before the war started. The Union dead would truly have “died in vain.”

With his heart in his hands and his hope all but lost, Lincoln’s thoughts turned toward reminding the nation of what was “proven by all history, that those nations are blessed whose God is the Lord.” As its President, while he was still its President, and for all he could do to preserve the moral ground that had been gained, if not literal ground, he sought to turn its head and heart to the God Who had established her privilege as a nation. America, for all of its prosperity and success, was still accountable before the Almighty, and its help and healing could only come from Him. The devastation of the war was God’s sovereign right to inflict, and it had come not without good cause. America’s good fortune had been forged through the arrogant exploitation of the powerless in her midst, and such vanity had to be broken. As a nation, we needed a reality check, and a restored reverence for the God Who made us, and had made us, each one, free. And God is reverenced in thanksgiving and praise.

And so in what was perhaps the darkest, most lonely, most rejected and seemingly hopeless time of his life, an all but beaten backwoods country lawyer, reviled by most, pitied by the rest, took pen in hand and issued a proclamation that the nation, now broken and battle worn, should humble its heart before the beneficent Father and be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged. He uncharacteristically signed this proclamation with his full name, usually merely “A. Lincoln.” But, as he had done with another proclamation just fourteen months earlier, entitled “Emancipation,” he inscribed his whole identity, and heart. When he had done so with the former declaration, he noted “If my name ever goes into history, it will be for this act.”

In the months which followed, the armies of a scruffy, cigar smoking, very ungenteel and somewhat lacquered subordinate general by the name of Grant were fighting their way through Tennessee and heading for Georgia and the heart of the Confederacy. Lincoln soon finally had a general he could trust. Later, as the new GeneralInChief of all Union armies, Grant directed a new drive against Lee’s troops in Virginia and was gaining ground toward the Confederate capital of Richmond. On the Western front, a trusted fellow general of Grant’s by the name of Sherman began advancing from Tennessee into Georgia to strike at the center of Atlanta. Then driving north into Virginia, he began to press the life out of rebel forces. Stubborn fighting continued and more than a hundred thousand more lives were lost, but by Election Day a year hence, the Union was gaining overwhelming momentum, and Lincoln’s policies were vindicated. After his re-election, he was then able to press for the 13th amendment to our Constitution, outlawing slavery permanently. At his inaugural, he spoke healing words to a war-torn nation. “With malice toward none, with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations…;” fitting words for any nation to pray and strive for.

A month after this speech, Lee surrendered to Grant. Five days later, on April 14, 1865, it was Good Friday, the celebrated day of Jesus’ death on a Roman crucifix that broke the bondage of sin and death over those who would trust in Him. “Lincoln arose early as usual, so he could work at his desk before breakfast. He was looking forward to the day’s schedule. That afternoon he would tell his wife, ‘I’ve never felt so happy in my life’.” That night, at Ford’s Theater, as he, Mary and guests attended a comedy play which he was uproariously enjoying, he was dispatched to the ages.

A Thanksgiving Proclamation was made by most of our first Presidents for the first thirty years of our history as a nation. No more were made after 1815 until President Lincoln reinstituted the tradition during his tenure in office, declaring Thanksgiving a Federal holiday as a “prayerful day of thanksgiving” on the last Thursday in November. Since then, every U.S. President has issued one on behalf the nation. The permanent date of the fourth Thursday in November was set by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 and approved by Congress in 1941. Here then is the proclamation revitalized by President Lincoln, in the midst of what was one of the darkest times of our nation’s history, and of the President himself. God’s hand moved to preserve the Union and remove the terrible blight of human slavery across the land. We do well to acknowledge that Power, and the gracious blessings of healing and prosperity that can only come from Him. How blessed indeed is the nation whose God is the Lord.

Thanksgiving Proclamation 1863

It is the duty of nations as well as of men to own their dependence upon the overruling power of God; to confess their sins and transgressions in humble sorrow, yet with assured hope that genuine repentance will lead to mercy and pardon; and to recognize the sublime truth, announced in the Holy Scriptures and proven by all history, that those nations are blessed whose God is the Lord.

We know that by His divine law, nations, like individuals, are subjected to punishments and chastisements in this world. May we not justly fear that the awful calamity of civil war which now desolates the land may be a punishment inflicted upon us for presumptuous sins, to the needful end of our national reformation as a whole people?

We have been the recipients of the choicest bounties of heaven; we have been preserved these many years in peace and prosperity; we have grown in numbers, wealth and power as no other nation has ever grown.

But we have forgotten God. We have forgotten the gracious hand which preserved us in peace and multiplied and enriched and strengthened us, and we have vainly imagined, in the deceitfulness of our hearts, that these blessings were produced by some superior wisdom and virtue of our own. Intoxicated with unbroken success, we have become too self-sufficient to feel the necessity of redeeming and preserving grace, too proud to pray to the God that made us.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that God should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged, as with one heart and one voice, by the whole American people. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November as a day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father Who dwelleth in the heavens.

- Abraham Lincoln